thisconstFirst of all, a simply truth. Everything in your program exists somewhere in memory. In C++ we can ask the question (and get the answer) as to where.

To be honest, we as humans don't usually care where something is. Doesn't matter whether the address is 1234567 or 7654321. But it is convenient for our programs to be able to remember where things are so that we can find them. Another point of view is the old physics adage that no two things can occupy the same space. So, if we know that two "things" are at the same location, we also know that really they are the same thing.

So, what does all that add up to in programming terms?

Ok, that's the starting point. How do we do each of those things?

C/C++ has an address-of operator. It is the

and-sign, &. If you put the

and-sign (or address-of operator) in front of any variable, then you

are asking what address is that variable stored at in the currently

running program. Consider this code snippet:

int x = 17; cout << x << endl;

cout << &x << endl;

The first line defines an int variable x and initializes it to the value 17. The second prints out the value 17. What about the third line? When I put those lines in a program and ran it just now, the last line output:

0xbffff7fc

The first two characters 0x indicate that this is being displayed as a hexidecimal value (i.e. base 16). If you run the program, you might get a different value. Also, if we don't like hexidecimal, we could ask for it to be displayed in decimal or in octal notation, but I won't bother you with how to do that here.

So, how can we remember where x is if we want to access it later? In the last section, we printed out the address of x. Now lets store that value in a variable. Simply put, we would like to be able to write

int x = 17; cout << x << endl;

cout << &x << endl;

p = &x; // This line won't compile. Why?

cout << p << endl;

We wrote a line that stores the address of the variable x into the variable p. But the comment in the code says that this won't work. Why won't it? C++ requires that every variable be defined with a type before it can be used. We haven't yet identified the type of p. We need a new piece of syntax. The correct version of that line should be:

int* p = &x; // Now we've got it right

The asterisk after the type int identifies this as a new kind of type, one that can hold addresses. The variable p is known as a pointer.

We might say that there is no such thing as "a pointer". Instead there is a "pointer to int" or "pointer to Elephant" or... Yes we will often refer to "a pointer" but we are nearly always really talking about a pointer to something.

One exception is when we ask “how large is a pointer?”. Addresses on a given machine are all the same size, so pointers are all the same size, no matter what they point to. On the Pentium, pointers are 32 bits (or 4 bytes).

We are just about done. We can get the address of something. We can store the address into a variable. Now we just need to be able to access the thing that a pointer is pointing to.

int x = 17; cout << x << endl; // Displays 17

cout << &x << endl; // Displays the address of the variable x

int* p = &x; // Stores the address of x in the variable p.

cout << p << endl; // Again, displays the address of the variable x

cout << *p << endl; // Displays the value 17

The last line shows the new syntax. Again we are using the asterisk. But we are using it in a different way than we did before. Before, it was being used as part of the type. Here, it is known as the dereference operator. It can only be used with a poiinter variable (or an address). It's purpose is to access or retrieve the thing being pointed to.

There is one special value that we can assign to any pointer

variable. nullptr. It represents an address

that cannot be used. Note that in common speach, we

generally say "null", even though we mean the

symbol nullptr.

If you try to dereference a null pointer, then your program will

crash. (A good thing.) Whenever we have a pointer and don't have

anything to point it to at the moment, we should set it

to nullptr. Be sure to remember this when defining a

pointer variable, or initializing an object that has a field that is

a pointer.

NB: Prior to C++11, there was no such symbol

as nullptr. "Back then" you had to use a symbol

called NULL. The reasong for the change is that the

compiler can detect certain kinds of errors if we use the new symbol

that it could not with the old one. I won't trouble you with the

details of this improved error checking; just accept that the more

errors the compiler can catch, the better.

But a great deal of code and writing uses the old symbol, since the

change over is fairly recent. That includes code and writing on

this website. Quite simply, any code you are writing should

use nullptr, but you should not be surprised to

see NULL in use for years to come.

That's it for the basic notation! A couple of other syntactic points are worth noting.

We have been using the following for defining a pointer variable, a pointer to an int, that is:

int* p; // My preference.

Personally I like this style because it makes instantly clear the type of the variable that we are defining. There are other ways of defining the same variable and there are people who prefer them. One approach is to place the * directly next to the name of the variable:

int *p; // A common alternative.

People who prefer this approach tend to like it because it is glaringly obvious that the variable is a pointer of whatever type.

Another reason to prefer placing the asterisk next to the variable comes up in confusion that can arise from the following line:

int* p, q; // This may not mean what you think it does

The line above defines a variable p that is a pointer to an int and a variable q that is an int, not a pointer. If we used the second style then that line would look like

int *p, q;

Here it is much clearer to the eye that only the first variable is a pointer. (Not good to define things of more than one type on a line. And frankly, it is better not to define more than one thing on a line in any case.)

But I mentioned three options. The third one, I find odd at best. However, I have seen it used in a number of places. Perhaps the authors did not want to commit to one or the other of the above options. The third option is to place a space one each side of the asterisk. Looks to me like an odd bit of multiplication.

int * p; // Multiplication? No, we are again defining p to be a pointer to int.

Suppose we have a Person class:

Suppose we want to access a Person object using a pointer:class Person { public: Person(const string& name) : name(name) {} void display() const { cout << "Name: " << name << endl; } private: string name; };

How do we call the display method for george using the pointer variable? A first thought is that we need to dereference the pointer, then we can access the member. Following that thought we would try:int main() { Person george("George"); Person* ptr = &george; // Now we would like to display george using ptr. }

// Now we would like to display george using ptr. *ptr.display(); // This is NOT correct.

As the comment says, that's not quite correct. The problem is the same as if I wrote 1 + 2 * 3 and wanted the answer to be 9. What's the problem? Back when I was in elementary school, they called this Order of Operations. In computer science we refer to this as precedence. Whatever you call it, we all know that without parentheses, multiplication gets done before addition. Same thing with the "dot" operator and the dereference operator, the dot gets done first. But we want to do the dereference first. We could rewrite that as:

// Now we would like to display george using ptr. //*ptr.display(); // This is NOT correct. (*ptr).display(); // Works but is considered ugly.

As the comment says this time, that'll work but programmers don't want to have to bother with parentheses for somthing so common (except for lisp programmers). Instead, we use a different operator that does away with the parens, the * and the dot:

// Now we would like to display george using ptr. //*ptr.display(); // This is NOT correct. (*ptr).display(); // Works but is considered ugly. ptr->display(); // GOOD

That's the correct way to write it.

thisSometimes when we are inside a method, we need to be able to refer to the object we are being called on. Using the Person class above, inside the display method we can easily refer to the name of the object we are being called on. But what if we wanted to refer to the whole object? That is the purpose of the keyword this. It is a pointer that points to the object that the method is called on. For example, if we wrote the function call: george.display(); while inside that call to display, this would be pointing at george.

Occasionally, people will use this to make clear when their code is refering to a member. Let's write a setter for the name field of the Person class. (No, I don't think this is a good idea unless you really intend to let people change their names.)

In this case, we called the parameter aName in order to distinguish it from the member called name. We could instead also call the parameter name if we use this to keep straight which is which:class Person { public: Person(const string& name) : name(name) {} void display() const { cout << "Name: " << name << endl; } void setName(const string& aName) { name = aName; } private: string name; };

By using this to clarify when we are referring to the member variable, we were able to use name for the parameter that we did for the field. Some people like this sort of thing, others think this style is bad idea. But it does show how this can be used.void setName(const string& name) { this->name = name; }

Let's add an "association" to the Person class.

[For now, look at the code that we developed in class to allow two people to get married Also look at the separate notes on Association and Composition.]

When we thinking about the use of const and pointers, there are two different ways that we can apply const to a pointer and they each have a different meaning.

Making a variable const generally means that we cannot change the value that it holds. In this sense, to make a pointer const, we want to make it so that once the pointer is set, actually once it is initialized, it can never hold a different address. It can never point to a different thing in memory. In order to do that, we have something like:

int x = 17, y = 6;

int* const p = &x; // p is const. Can only point to x.

*p = 42; // Fine. We are changing the value in x, not the value in p.

p = &y; // Will not compile. p is const so we cannot change its value.

Notice that the const was placed after the asterisk.

But there is a second use for const and pointers. It is similar to when we define the type of a reference parameter to be const. The idea is that when using the pointer variable, we want to make sure that we cannot change the value held in the thing we are pointing at. Here is an example very similar to what we just did, but also very different

int x = 17, y = 6;

const int* p = &x; // p will treat x as const.

*p = 42; // Will not compile. We cannot change x, using p.

p = &y; // Fine. We are changing the address in p, not the value in x.

Notice that this time that the const was place before the astersik. In fact it is normally placed as we did before the type (int in the case) of the thing we will be pointing at.

Of course we can do both:

int x = 17, y = 6;

const int* const p = &x; // p can only point to x and will treat x as const.

*p = 42; // Will not compile. We cannot change x, using p.

p = &y; // Will not compile. p is const so we cannot change its value.

Not everything can exist on the call stack. Why? When we define a local variable, it can only exist as long as the current function is running. To solve that problem, there is another part of memory, called the heap, where we can put things that allows us to keep them around as long as we like. For now, I want to just focus on how we use the heap. You will come to appreciate its value as we go along. Oh, the heap is also know as dynamic memory or free store. (I tend to use heap, most often, but I also say dynamic memory. Stroustrup uses free store.)

To create something on the heap, we use new, which is an operator and also a keyword. (Being a keyword means that you can't use it for the name of a variable, parameter, function or type.)

int* ptr = new int(17);

Here we have used new to allocate space on the heap to hold an int and we initialized the int to 17. The keyword new returns a value, the address of the thing we just created. We always want to store that address somewhere right away because without the address, we cannot access what we put on the heap. Now that we have a pointer to this int, we can do any of the things we have learned to do with pointers. For example we can print it, modify it and then print the new value with:

cout << *ptr << endl; // Print the thing pointed to by ptr *ptr = 42; // Change the location pointed to by ptr to hold 42 cout << *ptr << endl; // Print the thing pointed to by ptr, again

Remember that one advantage of using the heap is that the things we allocate there "live" until we want to get rid of them. How do we free things up from the heap?

delete ptr;

That's it. Use delete, passing it the address of whatever you want to free up from the heap. Note that the address better refer to something on the heap or what you have done is very wrong and will probably crash your program.

There is the question as to what happens to the value inside the pointer variable itself, that is what happens to the address that the variable is holding? We have said that the thing that is being pointed to is "freed up" but what about the contents of the variable? The answer is simple. Nothing. Nothing happens to the variable. It is not set to NULL. It still points to the same location on the heap that it did before.

What if we try to access the location on the heap after we free it up? First, don't. It is an error in programming to try. Now, back to what will happen. I can't tell you. Your program may find the old data still sitting there. Your program may find that the data has changed. Your program may crash. Unfortunately, the compiler cannot catch this error for you, no matter how obvious it is. And unfortunately, it is not well-defined as to what will happen.

A pointer that used to point to something valid but doesn't anymore is normally refered to as a dangling pointer. Dangling pointers are dangerous. If the pointer is going to be around for a while, then it should be set to NULL. At least then if we try to access it, we can be sure that the program will crash (a good thing here).

Also, do not try to free up the same thing more than once.

delete ptr; delete ptr; // BAD!!! Do not call delete more than once on the same address.

Ok, the one (and only) time you can call delete more than once on the same address is if that address is null (i.e. the nullptr).

ptr = nullptr; delete ptr; delete ptr;

Earlier we talked about how to fill a vector of objects from a file, when using encapsulation. And before that we talked about how to do the same thing with structs, i.e. how to fill a vector of structs from a file.

Now we should do the same thing with a vector of pointers. The question is if we are using pointers, what will we point at? If we are reading the information from a file, then there aren't any objects yet to point to. Let's consider one possibility (a wrong wa of doing it). We will base it on the Person class above.

// BAD code!!!! void fillPersonVector (ifstream& ifs, vector<Person*>& vc) { string name; // Used to read in the name while (ifs >> name) { Person aPerson(name); // Person object defined inside loop. vc.push_back(&aPerson); // BAD!!! Pushing the address of the local variable } }

The code above is marked BAD. Why? There are two reasons. First, when we finish the function call, all local variables cease to exist, along with the values/objects they held. So, those addresses aren't of any use anymore.

There's another problem. The addresses that we are pushing onto the vector each time are always the same. It may not be obvious, but the Person that we are initializing each pass through the loop is at the same location every time.

So, what can we do? We can create the objects on the heap.

void fillPersonVector (ifstream& ifs, vector<Person*>& vc) { string name; // Used to read in the name while (ifs >> name) { Person* ptr = new Person(name); // new Person object defined each time through the loop. vc.push_back(ptr); // Good } }

Now we can write a function to loop over the vector, printing out all the people. Note the use of the arrow operator:

void displayPersonPointerVector (const vector<Person*>& vpp) { for (size_t index = 0; index < vpp.size(); ++index) { vpp[index]->display(); } }

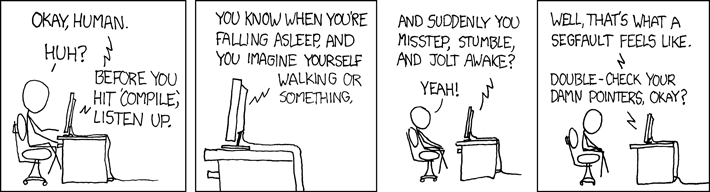

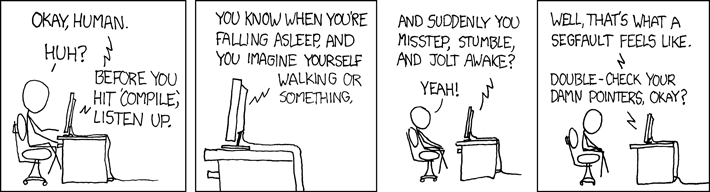

There are two problems that come up with using pointers all of the time. The first is when you use a "bad" pointer. Simplest case of a bad pointer? One that you have never initialized, so it is holding some random junk and probably pointing to nowhere useful. Xkcd said it pretty well with:

Yes, you have to check your pointers. Make sure they are pointing where you want them to.

The other common problem is a memory leak. Consider the following code:

Thing* p = new Thing(); p = new Thing();

What just happened? We lost the first thing! That's a memory leak. That one may seem really stupid. This next one is just as stupid, but more likely to happen:

void foo() { Thing* p = new Thing(); }

Doesn't matter how it happens, memory leaks can be a big problem for your program.

There are a number of things about pointers that we have not yet discussed.

int* q;

int **r = &q;Error: *x/*y (Why?)Maintained by John Sterling (jsterling@poly.edu). Last updated February 26, 2014